By Jeffrey B. Riley, Ph.D

Professor of Ethics and Associate Dean of Research Doctoral Programs, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary

Earlier this year Pediatrics, a journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, published an “Ethics Round” in which a Dutch pediatrician and philosophers from the United States and the Netherlands debated the ethics of killing children who are “experiencing unbearable suffering.” The evolution of euthanasia in the Netherlands prompted this topic. In 1984 a doctor was charged for assisting in the suicide of a 94-year-old woman. Supported by the Royal Dutch Medical Association, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands acquitted the attending physician, which in essence normalized the practice of assisted suicide and opened the door for voluntary euthanasia. Voluntary euthanasia is the practice of killing patients at their request who are incurably ill, in great pain or under physical or mental distress. In short, exchange a “bad life” for a “good death.” In 2002 the Netherlands legalized voluntary euthanasia for residents 12 years of age and older. In 2005 the Dutch legal and medical professions embraced the Groningen Protocol, which established procedures for reporting neonatal euthanasia — infanticide for babies under one. Though not codified in law, parents and doctors can kill children under the age of one who are diagnosed with severe illness or expected to face a future of suffering and hardships. In “Ending the Life of a Newborn,” bioethicists Hilde Lindemann and Marian Verkerk explained that three classes of newborns can be euthanized under the Groningen Protocol: 1. those who have no chance of survival; 2. those who “may survive after a period of intensive treatment but expectations for their future are very grim”; 3. those “who do not depend on technology for physiologic stability and whose suffering is severe, sustained and cannot be alleviated.” In other words, on the judgment of adults, a child who faces a “life not worthy of living” could be killed. Now some authorities, such as those in the Netherlands, want to close the age gap to include killing children one to 12 years old.

A look at the transformation

In his Summary for [the U.S.] Congressional Subcommittee on the Constitution: Suicide, Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, Dr. Herbert Hendin states that “the Netherlands has moved from assisted suicide to euthanasia, from euthanasia for the terminally ill to euthanasia for the chronically ill, from euthanasia for physical illness to euthanasia for psychological distress and from voluntary euthanasia to nonvoluntary and involuntary euthanasia.” The late British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge stated candidly that it took only a few decades “to transform a war crime into an act of compassion,” and the Dutch are not alone.

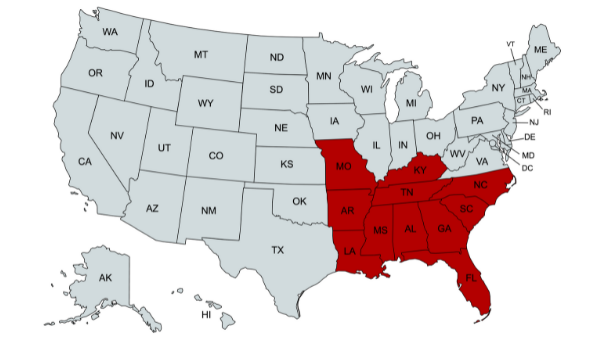

To date, euthanasia is legal in the Netherlands, Belgium, Colombia, Luxembourg, Canada, India and South Korea. Although euthanasia of any type and for any age remains illegal in the United States, physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is permitted in Washington, D.C.; California, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, Hawaii and Washington. In Montana the state Supreme Court allows PAS by fiat; the courts do not prosecute physicians who assist in suicides. PAS, in contrast to euthanasia, entails providing lethal drugs to patients who can elect to end their lives at a time of their own choosing.

Although the legalization of euthanasia internationally has been slow to emerge, many bioethicists and cultural progressives defend the use of medical interventions to end suffering at any stage of life, including infancy and childhood. In 2012 bioethicists Alberto Giubilini and Francesca Minerva published a defense of infanticide in the BMJ (formerly British Medical Journal), calling it “after-birth abortion.” Following the logic of utilitarian philosophers such as Peter Singer and Michael Tooley, Giubilini and Minerva see no distinction between an unwanted pre-born baby and an unwanted infant. In other words, they justify infanticide in the same way as legalized abortion. Ironically, they agree with the pro-life argument that birth itself changes nothing about the personhood of the child. They simply do not believe that a baby, whether pre-birth or post-birth, is a person who has a right to life and should be protected by law. Why? Giubilini and Minerva stated that newborn babies are not actual persons. They define actual persons functionally, as able to reflect on and value their own existence. A newborn’s life can be taken because he or she does not really suffer the loss of personal value or plans. For Giubilini and Minerva, infants are only potential persons, not actual persons with potential. In their final analysis, infanticide is justified by any reason abortions are justified: concern about unwanted or too many children, inability to care for a child, lack of support from family, fear of lost dreams, personal autonomy of the mother and so forth. Peter Singer, in Practical Ethics, made similar arguments denying the personhood of infants. His basic point is that if disabilities justify abortion, then similar disabilities should justify infanticide. For Singer, parents should be allowed to replace disabled children with healthy children, at least up to a point before which a child becomes self-conscious.

Appeal to our emotions

Guibilini, Minerva, Singer and other leading bioethicists — though not all — propose disturbing justifications for infanticide, bolstered by a view of the world that is foreign to Christians and strange to many Americans who know intuitively that being born and being alive matter. By contrast, the proponents of infanticide or child euthanasia in Pediatrics make an appeal to our emotions that is far less repulsive and honest than the candid arguments of the bioethicists mentioned here. For example, in the Pediatrics article, philosopher Margaret Battin communicated that no sane person wants to suffer, we should alleviate suffering, parents do not want to see their children suffer, sometimes we just want to die and sometimes we think that one who suffers excessively without hope is better off dead. In all honesty, most Christians agree more or less with these statements; nevertheless, none of these statements justify killing a child. Proponents of infanticide use statements about suffering not only because they believe them to be true but also because their opponents do too. To hear these kinds of statements creates a sympathy for proposals supporting infanticide in particular and euthanasia in general. The arguments of Guibilini, Minerva and Singer do not really find traction among Christians, but we sympathize with sufferers. Even so, we should not justify killing human beings by saying that we do not like suffering, that we could not bear to suffer in the way we have seen in others or that we cannot bear to see our child in pain and without hope of a normal life. The desire to end suffering does not justify killing as the means, and neither does the admirable motive, compassion.

Think as Christians

We must move beyond emotional sound bites and the smoke and mirrors of euphemisms to think as Christians about suffering and death. Most of us already think of these certainties to some extent. Many already experience them — loved ones infirmed and never again themselves, bodies in relentless pain, infants with incurable and debilitating diseases and so forth. These difficulties are human, not merely Christian, yet they beg for a response braced by Christian beliefs and seasoned with sympathy for those who suffer. One might think that the confessions of our faith are only for Christians and therefore not allowed in public debates over euthanasia or infanticide, but how we treat those who suffer is not a church-state issue. For Christians to speak as Christians about life and death issues in the United States does not establish a particular religion but is an expression of the speaker’s identity and an exercise of free and honest speech. The goal is not to make laws but to treat human beings as they ought to be treated. So, what ought we to say to our family, friends, neighbors and fellow Americans about this debate on infanticide and child euthanasia? Perhaps more importantly, what do we say to parents who grieve over a suffering child?

I first must confess that here I can offer only a general frame of reference because a book’s worth of information and argumentation undergirds the conclusion that child euthanasia is wrong and ought not to be practiced. The unanswerable question is why a particular child suffers or dies. Each life and death is unique and personal, but an implication of the message of the gospel is that any sufferer can embrace the grace, kindness and wisdom of God, trusting that Jesus Christ, who is the Resurrection and the Life, loves the little children and weeps for those who weep. Beyond embracing and trusting, in the midst of pain and unanswered questions, silence with prayer is needed to find peace. Before the tempests come, we do well to consider our moral response to euthanasia.

We should be clear about what is spiritually at stake in euthanasia. Christians confess that every human being is created in the image of God and may be redeemed through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, no matter how old, physically or mentally debilitated, afflicted or distressed. The creation and redemption of God establishes the dignity of every human being, and neither suffering nor physical or mental impairment diminishes that dignity. Creation and redemption point us to a God who loves and is able to sustain those who suffer physically and emotionally. God’s grace is available in the hour of need, not before. Moreover, our creation in the image of God makes us responsible for one another. That responsibility is to comfort with help, not to kill. The death of a human being is serious business; to take a human life intentionally without authority granted by God is a capital offense in the eyes of God (Gen. 9:6; Ex. 20:13). The Bible is clear: the great commandments to love God and your neighbor satisfy the sixth commandment not to murder. In other words, care for — don’t kill — your suffering neighbor. Because of the image of God, suicide is a murder of the self, assisted suicide involves an accomplice to murder and euthanasia is simply murder in the eyes of God. God alone has the authority to give, take and authorize the taking of life, and God alone “will bring every act to judgment, everything which is hidden, whether it is good or evil” (Eccles. 12:14).

We should meet the physical and emotional needs of those who suffer. Actions, perhaps more than words, authenticate the Christian message to those who suffer. In the face of pain, rather than call on death, we should demand a palliative care that minimizes pain. Palliative care, however, is not enough. Pain is not the primary motivation for euthanasia. According to oncologist-bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel, the primary motivation for euthanasia is depression and general psychological distress over being a burden, being dependent or losing control or dignity. In this case, patients need emotional care, not death. Infants, children and adults should be affirmed, nurtured and counseled, not killed. Hospice provides this kind of care. For infants and children, who do not naturally think of being a burden, being independent or losing control, parents and family provide primary soul-care. In all cases, churches should support families, providing a spiritual care that entreats and represents the grace and mercy of God. The promises of God can defeat the hopelessness that so often accompanies suffering. The presence of God and God’s people can overwhelm the loneliness of death and dying.

Jesus defeated death

Jesus Christ alone ultimately calms fears and fulfills hopes. Jesus defeated death. Death is not the savior of sufferers. Death is not compassionate. More and more, the movers and shakers of cultural change demand the legalization of euthanasia, calling for a good, painless and compassionate death. Though inevitable, death, like suffering, is an enemy. The confession of our faith is that Jesus ultimately defeated these enemies. He is the Resurrection and the Life (John 11:25). As such, for us to live is Christ and to die is gain (Phil. 1:20–26). We should seek a death rightly suffered that bears witness to our trust in the One who is the Life, the Giver of life eternal and the Conqueror of death. A hopeful and faithful approach should shape our response to the suffering and death of loved ones. Faith and hope cannot take away the pain of seeing loved ones suffer — true love does not allow such emotional anesthesia — but the personal presence of our loving God in unexplainable ways provides sufficient grace to keep living. In the end, faith, hope and love ought to characterize the lives of Christians, who suffer patiently until the One who died for us comes to take us to be with Him (John 14).

The story of euthanasia in the Netherlands should serve as a warning. To Christians, who should hold to the dignity and value of every human being, it is unjustified and forbidden to kill someone deliberately merely because he or she is ill or dying. What happened in the Netherlands can, with the same legal sleight of hand, happen here. Popular indifference, justification by experts and elites, judicial sanction and legislative endorsement change the cultural view of life and create an environment where conflicting worldviews clash about God, the nature of the world and human identity. This is no slippery slope. This is the way cultures change. Followers of Jesus Christ are to be salt to a world in decay and light to a world slipping into darkness. Our primary message is the gospel; and to infants, children and adults alike, we should suffer that they come to Jesus on His gentle terms.

________________________

Meet the author

Jeffrey B. Riley is a professor of ethics and associate dean of research doctoral programs at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. He is the founding co-director of the Institute for Faith in the Public Square. He and his wife, Laura, have two children.

Share with others: