By Martha Simmons

Correspondent, The Alabama Baptist

When Michael Brandon Samra was executed at Holman prison in Atmore May 16, his last words were a prayer but no spiritual adviser was present in the chamber.

Samra’s spiritual adviser observed Samra’s death from a witness room, a change in protocol resulting from two recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions involving prison chaplains, executions and religious freedom. The cases involved two death row inmates — one in Alabama, the other in Texas — both of whom turned to the Supreme Court with requests to stay their executions until the states agreed to allow a spiritual adviser of each inmate’s own faith to accompany him to the death chamber.

Stay of execution

In Alabama, the inmate was Muslim. Domineque Ray was scheduled to die by lethal injection for the 1995 rape and murder of Selma teenager Tiffany Harville. His request to have his imam by his side ran afoul of the state prison system’s protocol that, in effect, required a Christian chaplain in the death chamber. Although they must work with a wide variety of faiths on a daily basis, all of the chaplains employed by the Alabama Department of Corrections are Christian.

The state’s execution protocol required a state-employed chaplain to be present in the death chamber but did not allow non-employees such as Ray’s imam to be present.

Claiming that his constitutional rights to freedom of religion were being violated, Ray was granted a stay of execution by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, which ruled unanimously that “it looks substantially likely to us that Alabama has run afoul of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.”

The three-judge panel went on to say, “The central constitutional problem here is that the state has regularly placed a Christian cleric in the execution room to minister to the needs of Christian inmates but has refused to provide the same benefit to a devout Muslim and all other non-Christians.”

Ray’s Feb. 6 victory was short-lived, the stay of execution overturned the very next day by the U.S. Supreme Court on a 5–4 vote. The court sidestepped ruling on the constitutionality of the protocol, however, deciding on Feb. 7 that Ray had not challenged the protocol in a timely enough manner. Ray, 42, was executed that same night with his imam watching from the viewing room and, in a concession by the state, no Christian chaplain present in the death chamber.

Criticism came swiftly and strongly from both the political left and right, as liberal law professors and conservative commentators alike proclaimed the decision a grave violation of the First Amendment. “Ray’s execution was just. The circumstances were not,” wrote David French in National Review. “The state’s obligation is to protect and facilitate the free exercise of a person’s faith, not to seek reasons to deny him consolation at the moment of his death.”

Different decision

Apparently stung by the criticism coming from all sides, the Supreme Court came to a very different decision in a very similar case just seven weeks later.

This time, the condemned man was Patrick Henry Murphy Jr., 57, a Buddhist in Texas.

Murphy was scheduled to die the evening of March 28 for his part in a seven-man prison escape followed by multiple robberies and the killing of 31-year-old Dallas police officer Aubrey Hawkins. By a 7–2 vote, the Supreme Court granted an eleventh-hour stay of Murphy’s execution because Texas would not allow his Buddhist spiritual adviser to be at his side.

Like Alabama, Texas prison officials would allow only a state-employed chaplain to be in the death chamber. Both Christian and Muslim chaplains were available, but not Buddhist.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who voted with the majority to overturn Ray’s stay of execution in Alabama due to the timing of his appeal, indicated that his support for Murphy’s stay was about freedom of religion. “As this Court has repeatedly held,” Kavanaugh wrote, “governmental discrimination against religion — in particular, discrimination against religious persons, religious organizations, and religious speech — violates the Constitution.”

Texas responded to the Supreme Court decision a week later by changing its policies to no longer allow any chaplain at all in the death chamber but allowing the condemned inmate to designate a spiritual adviser who may be present only in the witness room.

However, since the Supreme Court decision specifically called for allowing Murphy’s Buddhist spiritual adviser to actually accompany him in the death chamber, Murphy’s execution remains on hold.

Samra’s was the first execution in Alabama since the Court ruling in the Texas case. Previously ADOC said its policy on chaplains in the death chamber was under review.

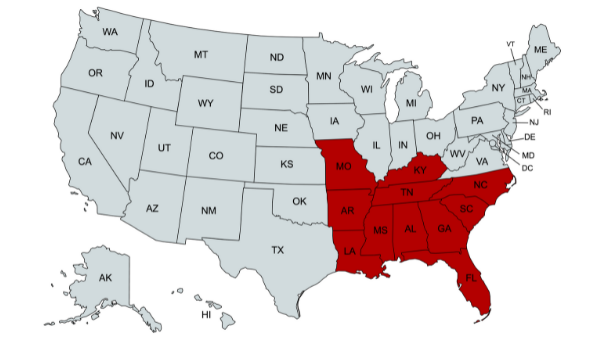

Following the Supreme Court decision in March, Stanford law professor James A. Sonne, founding director of Stanford Law School’s Religious Liberty Clinic, said most of the 30 states in which the death penalty is legal allow a chaplain of the inmate’s choice to be present at the execution, though that doesn’t necessarily mean in the death chamber.

Share with others: