By Neisha Roberts

The Alabama Baptist

The 500-year-long partnership and history bound up between the Church of Norway and its home country makes the recent split something some have called a messy divorce.

After an eight-year process, the Lutheran Church of Norway, the country’s largest denomination, separated itself from its country’s government Jan. 1 — thus a separation of Church and State. The Church will still receive some support from the State but the Scandinavian government will no longer employ 1,250 clergy and the Church will be considered an independent business.

The separation comes after a Parliament-approved 2012 bill was passed into law in January that amends the constitution, creating a “clear separation between Church and State,” according to Jens-Petter Johnsen, head of the Church’s National Council.

Other Norwegians disagree.

The revised constitution reads: “The Church of Norway … will remain Norway’s national Church and will be supported as such by the State.”

Kristin Mile, secretary general of the National Humanist Association, said, “As long as the Constitution says the Church of Norway is Norway’s national Church, and that it should be supported by the State, we still have a State Church.”

‘Culture war’ trigger

And although Norway is considered one of the least theistic nations in Europe, it does still have it’s own Bible belt along the southwest coast. So the constitutional change — from “the state’s public religion” to “Norway’s national Church” — could “inadvertently trigger a culture war,” according to Georgetown University professor Jacques Berlinerblau.

He told Religion News Service (RNS), “Certain anti-secular elements in Europe could point to Norway as an example of the ongoing collapse of Christian culture and Western civilization at the hands of diabolical secularists.”

The split will not take effect until June but will allow the Church the authority to name its own bishops and other leaders, without regard to the government’s final say, according to news sources. But Norway is not the only country that’s seen a split between religion and government.

There are dozens of countries that at one time had a “national religion” but have since been disestablished. According to the New World Encyclopedia, some of those countries are Armenia, Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Cuba, Guatemala, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Panama, the Philippines, Spain and Wales.

Globally there are still a handful of countries that have a national religion, “State Church” or “official religion” — Afghanistan (Islam), France (Roman Catholic Church), Malta (Roman Catholic Church), Scotland (Church of Scotland), Greece (Greek Orthodox Church), Yemen (Islam) and England (Church of England), to name a few.

These represent religious bodies or creeds officially endorsed by the State. Some countries, according to the encyclopedia, have more than one religion or denomination. And they are endorsed in a variety of ways — from financial support (with freedom for other faiths to practice), to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating to persecuting the followers of other faiths.

The relationship between a national religion and the nation in which it exists varies by location, according to Scott Leveille, executive assistant to the senior pastor at Covenant Presbyterian Church, Birmingham.

Eastern Orthodoxy in countries like Russia, Greece or Romania is “more closely related to each other than in Western contexts,” he said.

In Greece, for example, “There’s a real sense in which what it means to be Greek as a national identity is to be Orthodox,” Leveille told The Alabama Baptist.

Differentiate

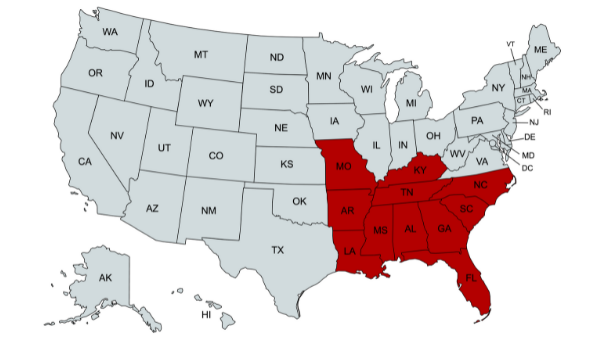

Even though the national religion is tied up in a person’s identity, Leveille said, “there’s a real nominalism … not so different than in the South (of the United States) where people self-identify as Christian or Baptist but may have never been in a church except for a baptism or a wedding.”

In Southeast Europe where Bosnians, Serbs and Croats are “ethnically the same people … they differentiate themselves based on religion,” Leveille said.

“A Serb may not say, ‘I’m a Serb,’ but instead say, ‘I’m an Orthodox.’ A Croat will say, ‘I’m Roman Catholic.’ … Again the religion becomes a marker of national identity.”

In Greece the government pays Greek Orthodox clergy from tax dollars and the Church in turn gives “limited rhetorical support to the government,” according to Gerald R. McDermott, Anglican Chair of Divinity at Samford University’s Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham.

There is some distrust between the Greeks and the Church, McDermott said, noting how some Greeks “point to alleged financial corruption by some Church leaders.” The Church, however, defends its use of money by noting how it cares for thousands of poor during the ongoing Greek financial crisis.

Combatting terrorism?

In Russia the Yarovaya Law introduced in 2016 was created to supposedly combat terrorism, but in turn made it illegal to preach, pray or share any religious material (outside certain areas) that are not Russian Orthodox.

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom chair Thomas J. Reese said the law will “buttress the Russian government’s war against human rights and religious freedom.”

Author David Aikman said in an interview with Christianity Today that the “Russian Orthodox Church is part of a bulwark of Russian nationalism stirred up by Vladimir Putin. Everything that undermines that action is a real threat, whether it’s evangelical Protestant missionaries or anything else.”

The measure will leave Russia’s evangelical minority at a disadvantage, according to New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary church history professor Lloyd Harsch.

“These laws reveal the continuing after-effects of communism, which viewed all religion as the same,” Harsch told Baptist Press. “If Muslims are bombing train stations, then restrict the religious activities of Buddhists and Christians [because] all religion [supposedly] is the same.”

Some other aftereffects of communism, Leveille said, are why some nations have such an emphasis on religion as it relates to national identity.

“When countries tried to rebuild after communism, they tried to have an identity different than before. … There was a real reemergence of nationalism … and the Church was a part of that (rebuilding).”

A lack of separation between Church and State, however, could mean the government controls the action, practice and bylaws of the Church. It also can mean the religion, whether it’s what you practice or not, can play an important role in the society in which you exist — governing laws around marriage, education, employment and countless other policies.

McDermott noted “upsides and downsides” to a country with a national religion.

The upside is that church leaders can speak out on national and international issues from the public square, which “enables the Church to show the relevance of the gospel to public life.”

The downside is that the Church “has incentives to support bad State policies that are opposed to the gospel,” he said, “and since [church leaders’] salaries are paid by the State, no matter how well or badly they perform, they have no incentive to work hard to evangelize and disciple.”

This leads to some religions, although they are considered national religions, maintaining a low “State Church” attendance. In the United Kingdom, for example, less than 1 in 10 people attend church, according to research reviewed by bbc.com.

However, if one examines Islam in Afghanistan, more than 99 percent of Afghans are Muslim. Other religions are prohibited, as are items that relate to another religion, like Bibles, crucifixes, carvings or other religious symbols.

The government in places like Afghanistan or Yemen has been “fearful of radical Islamic minorities who seek to overthrow the governments,” McDermott said. “They have walked a narrow line,” giving verbal support to radical Islamic teaching while hoping the rhetoric pacifies while not allowing them to replace the government with jihadist movements like the Taliban.

This is where some of the genius of America’s First Amendment shines through, McDermott said.

Separation of Church and State

“It prohibits a national religion … whereby federal tax dollars support a particular religion. No pastor’s salary is paid by the government. He or she must work hard to get and keep church members. All in all this is a major reason why American religion thrives.”

Leveille, however, noted how the Eastern Orthodox Church has historically exemplified the symbiotic relationship between Church and State.

“Church leaders understood that the State had a particular role to play but so did the Church. And only if they functioned together would the community function in a way that God intended.”

Share with others: