By Michael Frost

mikefrost.net

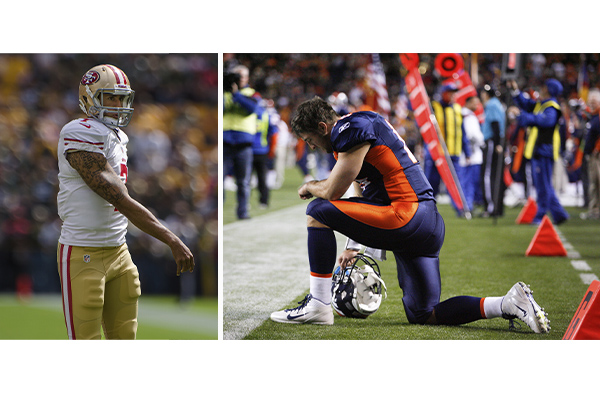

They’re both Christian footballers and they’re both known for kneeling on the field, although for very different reasons.

One grew up the son of Baptist missionaries to the Philippines. The other was baptized Methodist, confirmed Lutheran and attended a Baptist church during college.

Both have made a public display of their faith. Both are prayerful and devout.

This is the tale of two Christian sports personalities, one of whom is the darling of the American church while the other is reviled. And their differences reveal much about the brand of Christianity preferred by many in the church today.

First up, there’s Tim Tebow.

Tebow was homeschooled by his Christian parents and spent his summers in the Philippines, helping with his father’s orphanage and missionary work.

During his college football career, the Heisman Trophy winner frequently wore references to Bible verses on his eye black, including the ubiquitous John 3:16 during the 2009 BCS Championship Game.

He has been outspoken about his pro-life stance and his commitment to abstinence from sex before marriage.

He is a prominent member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, an organization which insists that leaders sign a Statement of Sexual Purity, stating that sex outside marriage and homosexual acts are unacceptable to God.

He has preached in churches, prisons, schools, youth groups and a welter of evangelical conferences.

And he is well known for his signature move — dropping to one knee on the field, his head bowed in prayer, his arm resting on his bent knee known throughout the world as “Tebowing.”

He’s clean cut, polite, gentle, respectful.

Then, there’s Colin Kaepernick.

Kaepernick, until recently the San Francisco 49ers quarterback, was born to a 19-year-old, single, white woman. His black father had left the picture before Colin was born. His mother was destitute and gave him up for adoption. He was raised by the Kaepernicks, a white couple from Milwaukee.

His body is festooned with religious tattoos, including depictions of scrolls, a cross, praying hands, angels defeating demons, terms like “To God be the Glory,” “Heaven Sent” and “God will guide me” (Ps. 18:39; 27:3).

Activist and philanthropist

He has said of his faith: “My faith is the basis from where my game comes from. I’ve been very blessed to have the talent to play the game that I do and be successful at it. I think God guides me through every day and helps me take the right steps and has helped me to get to where I’m at. When I step on the field, I always say a prayer, say I am thankful to be able to wake up that morning and go out there and try to glorify the Lord with what I do on the field. I think if you go out and try to do that, no matter what you do on the field, you can be happy about what you did.”

And Kaepernick’s faith isn’t just about making him feel happy. It’s turned him into an activist and philanthropist.

This year, during the offseason Kaepernick launched a GoFundMe page to fly food and water into suffering Somalia. It surpassed its $2 million goal in just four days. In March, the plane loaded with essential supplies landed in Mogadishu.

He had already pledged to donate $1 million, along with the proceeds of his jersey sales from the 2016 season, to charitable work.

Recently, Meals on Wheels announced it had received $50,000 from Kaepernick.

In September, he joined with the charitable organization 100 Suits, to pass out free suits in front of the New York State Parole office for people who have been released from prison and are looking for jobs.

But we all know why Colin Kaepernick is most famous.

Beginning in 2016, he refused to stand to attention during the playing of the American national anthem.

Kaepernick decided to either remain seated or kneel during on field renditions of the Star Spangled Banner in support of Black Lives Matter and in protest against police violence against black people.

He explained, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

He vowed to continue to protest until he feels like “[the American flag] represents what it’s supposed to represent.”

You know what happened next, right?

Kaepernick was voted the “most disliked” player in the NFL.

People posted videos of them burning his jerseys.

He was called “an embarrassment” and “a traitor.”

He was blamed for a significant drop in NFL television ratings, with fans boycotting the NFL because of his protest.

He received death threats.

Then, there’s Christianity on its knees.

It seems to me that Tebow and Kaepernick represent the two very different forms that American Christianity has come to.

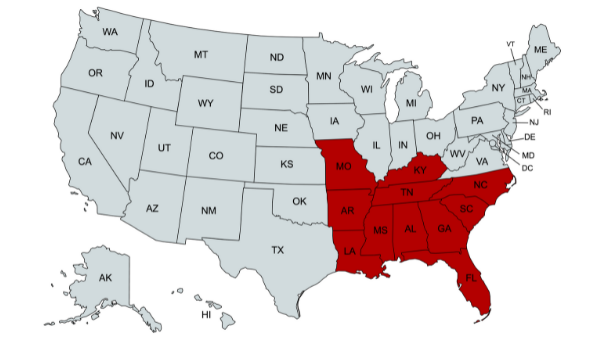

And not just in America. In many parts of the world it feels as though the Church is separating into two versions, one that values personal piety, gentleness, respect for cultural mores and an emphasis on moral issues like abortion and homosexuality, and another that values social justice, community development, racial reconciliation and political activism.

One version is kneeling in private prayer. The other is kneeling in public protest.

One is concerned with private sins like abortion. The other is concerned with public sins like racial discrimination.

One preaches a gospel of personal salvation. The other preaches a gospel of political and social transformation.

One is reading the Epistles of Paul. The other is reading the Minor Prophets.

One is listening to Eric Metaxas and Franklin Graham. The other is listening to William Barber and John Perkins.

One is rallying at the March for Life. The other is getting arrested at Moral Monday protests.

Contemporary Christianity

You can see where this is going. The bifurcation of contemporary Christianity into two distinct branches is leaving the church all the poorer, with each side needing to be enriched by the biblical vision of the other.

Biblical Christianity should be, as Walter Brueggemann expresses it, “awed to heaven, rooted in earth.” We should, as he says, be able to both “join the angels in praise and keep our feet in time and place.”

Sadly with the suspicion and animosity shown toward each side of the divide by the other I can’t see a coming together any time soon.

In the meantime, Christianity remains on its knees in the West. (Reprinted with permission)

Share with others: