By Kenneth B.E. Roxburgh

Special to The Alabama Baptist

Anglicanism emerged out of the 16th century medieval Catholic Church. The history of the Reformation in England in this period of time is a complex story involving religion, politics, the economy and international relations. Some historians argue the Reformation during the reign of Henry VIII was quick, imposed from above and that people conformed to the law of the land — not from the heart. Other historians maintain that over the course of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary Tudor and Elizabeth I, there were several movements of reform and only one was truly evangelical in nature, the rest being political.

Religious change in England took place within a context of the broader movement for reform on the continent of Europe. In England much change was piecemeal and it took 20 years to get to the first Protestant church service in 1552 which was reversed later by Mary Tudor. However, by 1558 when Elizabeth I ascended the throne the Reformation movement known as Anglicanism was to all intents and purposes intact. It was a mixture of Lutheranism and Calvinism, a kind of middle way between the old Roman Catholic ritual and the radical thinking of Protestantism.

The word “Anglican” originates in a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means “the English Church” but in the past two centuries the tradition has been adopted around the world. By the 21st century Anglicanism spread throughout the world with followers calling themselves “Anglican” or “Episcopal” in some countries such as Scotland and the United States. It comes under the umbrella of the Anglican Communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury as one of the leaders who seeks to hold a diverse movement together. Anglicanism unites itself under the 39 Articles of Religion, which emerged out of the 16th century, and centers around the common liturgy of the Book of Common Prayers service of worship with the central act of worship focused on the Eucharist, sometimes called “communion” or the “Lord’s Supper.”

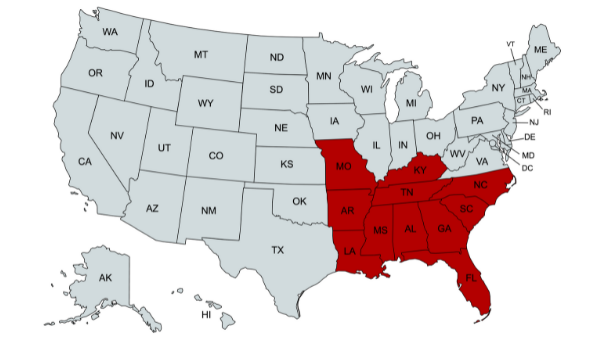

The Anglican Episcopal family consists of an estimated 85 million Christians who are members of 44 member churches (also called provinces) spread across the globe. In the U.S., Anglican worship was first celebrated on the coast near San Francisco by Sir Francis Drake’s chaplain in 1579. The first regular worship began in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Following the Revolutionary War, the new Episcopal Church was organized around a bishop consecrated by the Scottish Episcopal Church in 1784. It was at this point the Episcopal Church in the U.S. became fully autonomous. The Episcopal Church today includes 100 dioceses in the U.S. with just under 2 million members. Like many mainstream churches some congregations are growing, many are stable in membership and others are declining. Most conservative and evangelical religious bodies have been growing and mainline denominations have been in decline since the mid-1960s. There are proportionately more conservative Episcopal churches in the South and more liberal churches in the Northeast. Yet instances of growth as well as decline exist in all types of Episcopal congregations in the U.S.

Expressions of worship

Anglican doctrine is built upon Scripture, the ancient creeds of the Church, their distinctive ways of worship and doctrinal statements such as the 39 Articles of Religion. Scripture is acknowledged as the “ground” on which any expression of Christian faith must be founded. That faith is expressed during worship by using The Apostles’ Creed from the second century and the Nicene Creed from 382 as personal and corporate means of confessing the faith of the Church.

Although there are many modern expressions of worship used in Anglican congregations the Book of Common Prayer is a collection of services that worshippers in most Anglican churches have used for centuries. It was called “common prayer” because it was intended for use in all Church of England parishes. The term was retained because Anglicans worldwide used to share in its use. The form of worship found in the liturgy dates back to 1549 when the first Book of Common Prayer was compiled by Thomas Cranmer, who was then Archbishop of Canterbury under Edward VI. It has undergone many revisions and Anglican churches in different countries have developed other service books but the book is still acknowledged as one of the ties that binds the Anglican Communion together.

Anglicans observe both Baptism and the Eucharist. Baptism of infants is practiced, although in an increasingly secular context, especially in Europe. Anglicans also baptize those who have never had any connection to the Christian Church who come to faith in Christ and are baptized as believers either by immersion or by effusion.

Anglicanism is often referred to as a “Broad Church” because there are different groupings which come together to form the Anglican Communion. There are more evangelical Anglicans whose spirituality and theology connect strongly with the Reformation focus on Scripture alone, grace alone and faith alone. Evangelical Anglicans stress the importance of personal conversion and tend to have a more memorialist understanding of the Lord’s Supper. Secondly there are Anglo-Catholic Anglicans whose spirituality is influenced by the teaching of the early Church fathers. They tend to have a strong connection to ornate liturgy, the use of incense, kneeling to receive communion and frequent celebration of the Eucharist. They also express a strong desire for strong ecumenical relationships with the Roman Catholic Church because they see themselves as a part of this ancient Church. They view the English Reformation as a reformed continuation of the ancient “English Church” and not a new institution. Finally Liberal Anglicans maintain a theology which stresses the importance of Scripture and reason along with a passion for justice, human rights and pastoral care. This has led this wing of Anglicanism to support the ordination of women, the remarriage of divorced persons and the full inclusion of persons of different sexualities within the life of the Church. These diverse tendencies have in recent years caused divisions with Episcopalism in the U.S. and other parts of the world.

Anglican Church government is not congregational but hierarchical in which the chief local authorities are called bishops. The bishops will ordain ministers and confirm members at their first celebration of communion. Those members of the church who are called to pastoral ministry are first of all ordained as deacons and then ordained as priests in order to serve in local churches. Several Episcopal groups ordain both men and women to pastoral ministry although this has caused division among both Anglo-Catholics and evangelicals within the Episcopal Church in the U.S.

Trinitarian theology

Anglicanism holds to the cardinal doctrines of the Christian faith and especially a strong belief in Trinitarian theology. Along within the Nicene Creed they affirm a faith in each member of the Trinity declaring in the context of worship that the “Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life … who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified.” The debt which Anglicanism owes to the Protestant Reformation is clearly stated in their statement about justification in which they assert: “We are justified by faith only (which) is a most wholesome doctrine and very full of comfort.” Justification is linked to the work of Jesus Christ as the only means of salvation because “Holy Scripture doth set out unto us only the name of Jesus Christ, whereby we must be saved.” Anglicanism rejects an understanding of the Lord’s Supper which affirms transubstantiation. They do, however, hold that believers experience a special awareness of the presence of Christ when they take the bread and wine. For Anglicans communion is not merely an ordinance but also is a sacrament and so the bread and wine are given, “taken and eaten in the supper … in a heavenly and spiritual manner” and in this way believers may “feed on Christ in their hearts by faith with thanksgiving.”

In the 1980s the Anglican Communion reaffirmed its commitment to mission. It speaks of the Five Marks of Mission which include the proclamation of the good news of the Kingdom and the need to teach, baptize and nurture new believers; respond to human need by loving service; transform unjust structures of society; challenge violence of every kind; pursue peace and reconciliation; safeguard the integrity of creation; and sustain and renew the life of the earth. They view missions as a holistic expression of the love of the God for every spiritual, physical and emotional need of women and men in the world including the whole of creation.

Episcopal churches are likely to seek to work as closely as possible with other Christian denominations. In a document known as the “Lambeth Quadrilateral” adopted by Episcopalians in the U.S. in 1886 they state: “Deeply grieved by the sad divisions which affect the Christian Church in our own land, we hereby declare our desire and readiness … to enter into brotherly conference with all or any Christian bodies seeking the restoration of the organic unity of the Church.”

The current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, believes “living reconciliation can transform our world.” He has made it clear that “reconciliation doesn’t mean we all agree. It means we find ways of disagreeing — perhaps very passionately — but loving each other deeply at the same time, and being deeply committed to each other.

That’s the challenge for the Church if we are actually going to speak to our society which is increasingly divided in many different ways.” He views the importance of reconciliation and Christian unity as a prerequisite for effective evangelism in the 21st century.

Anglicanism is to be found in most communities where Baptists express their faith. Their congregations may not be as numerous as Baptist churches in the South but the expression of their faith is a vibrant understanding of their love for God, their faith in Christ and their obedience to the mission of the Holy Spirit in the world.

EDITOR’S NOTE — Kenneth B.E. Roxburgh is professor of religion at Samford University in Birmingham and serves as pastor for preaching and teaching at Southside Baptist Church, Birmingham.

Share with others: